Running Commentary 4/22/2024

Hello,

This past week, I hit a bit of a personal milestone: I have now seen 150 different species of birds in the wild (out of a possible total of ~11,000 in the world, but still...) having seen a savannah sparrow for the first time on Thursday. Yes, fittingly this milestone bird was a random sparrow that I may well have seen before but not identified. I came across a pair of them while looking for eastern meadowlarks near an airfield (that's bird 149, which I first saw the week before; more about that in this week's Bird of the Week). The count of 150 does not include birds seen in zoos or pet stores.

If you're interested, I have my life list and a record of interesting bird sightings tracked in the Birding Log linked to from the top of the page.

Anyway...

Watching...

The Bad Batch

- This episode was very tense, both on Omega's end and on the Batch's. Lots of sneaking around, lots of almost getting caught. It was largely setup for the series finale, which is coming fast with only two episodes left. My biggest hope for the finale is that, after all this setup of how secure Tantiss is that breaking everyone out is treated as significant and difficult. Our heroes are not approaching Weyland with overwhelming force, so they're going to have to do something clever. Then again, they might start with broadcasting Tantiss's location to someone else, like Rex. They probably won't, since that would give up their surprise advantage.

- There's been a lot of parallels between Omega's story here and Casssian's story in the latter half of Andor Season 1. Next episode we're bound to get a prison break. Somehow I doubt it'll be as good as "one way out" but we'll see.

- Rampart's a little too cartoon villain here, compared to how genuinely scary he was in Season 2. I honestly wonder what they'll do to him once the show gets everyone to Tantiss.

- I've got to wonder if Emerie knew Omega stole that pick from her tray. I suspect she did, but let it go

Reading...

Timekeepers by Simon Garfield

My immediate thought upon completing this book is that I found it a bit disappointing. Now, whether a reader finds a book disappointing is only half a function of whether the book was any good; it's also a function of reader expectation. I went into Timekeepers expecting a history of timekeeping, a history of the clock and calendar, more-or-less. Timekeepers dances with being such a book, but it's also a lot more loosely conceived than that. Here's the publisher's summary:

Not so long ago we timed our lives by the movement of the sun. These days our time arrives atomically and insistently, and our lives are propelled by the notion that we will never have enough of the one thing we crave the most. How have we come to be dominated by something so arbitrary?

The compelling stories in this book explore our obsessions with time. An Englishman arrives back from Calcutta but refuses to adjust his watch. Beethoven has his symphonic wishes ignored. A moment of war is frozen forever. The timetable arrives by steam train. A woman designs a ten-hour clock and reinvents the calendar. Roger Bannister becomes stuck in the same four minutes forever. A British watchmaker competes with mighty Switzerland. And a prince attempts to stop time in its tracks.

Timekeepers is a vivid exploration of the ways we have perceived, contained and saved time over the last 250 years, narrated in the highly inventive and entertaining style that bestselling author Simon Garfield is fast making his own. As managing time becomes the greatest challenge we face in our lives, this multi-layered history helps us tackle it in a sparkling new light.

That's not a bad description of what this book is, but, to me, it promised a through-narrative about how timekeeping changed human society, which just wasn't present throughout the book.

Garfield doesn't just write about clocks; he writes about people's relationship with time in all its forms. That's a lot for an author to get his head around, and I don't feel like Garfield quite did get his head around it. The chapters are quite disconnected, and the sections within chapters are sometimes also only tenuously connected. There are two chapters about Swiss wristwatches (one about their manufacture and one about their marketing), a chapter about music tempo that turns into a chapter about the duration of music recordings, a chapter about Roger Bannister's four-minute mile, a chapter about photography and the way it can preserve an instant for all time, a chapter about workplace time management and another about personal time management, a chapter about time zones, and a chapter about calendars, among other chapters (15 in all). For the most part, these chapters are interesting stories, but they just never came together as a book for me.

Garfield's writing is very readable and has a nice personal touch in a lot of places. It's not very evidently well-researched. There are some footnotes and some listed bits of further reading, but there are fewer of these than in other such books I've read. I don't think Garfield made things up, but citations were a little scarce. Then again, this isn't an academic work. It's more like someone took a bunch of magazine columns and put them in a book. Timekeepers was an interesting read but a rather middling non-fiction title and far from the last work on the story of timekeeping. I don't regret reading it; I enjoyed it, and I even sort of recommend it as a grab-bag of interesting narratives, but it's not much more than that. 6/10

Bird of the Week

There are a few ways to see lots of birds, if that's a goal of yours. You can travel widely, and see the common birds around the world. You can pick a birdy spot and visit it frequently, spotting all the birds that visit that locale. You can monitor birding reports online and go chasing after anything you haven't seen. But none of these strategies is a sure thing. You might, indeed I say you will go looking for a bird and not find it. It's not a happy thought, but its a familiar experience to most birders. But, on the other hand, it's also possible that you'll see a bird when you weren't even birding. That's what happened to me recently when I took my first look at today's bird: the Eastern Meadowlark.

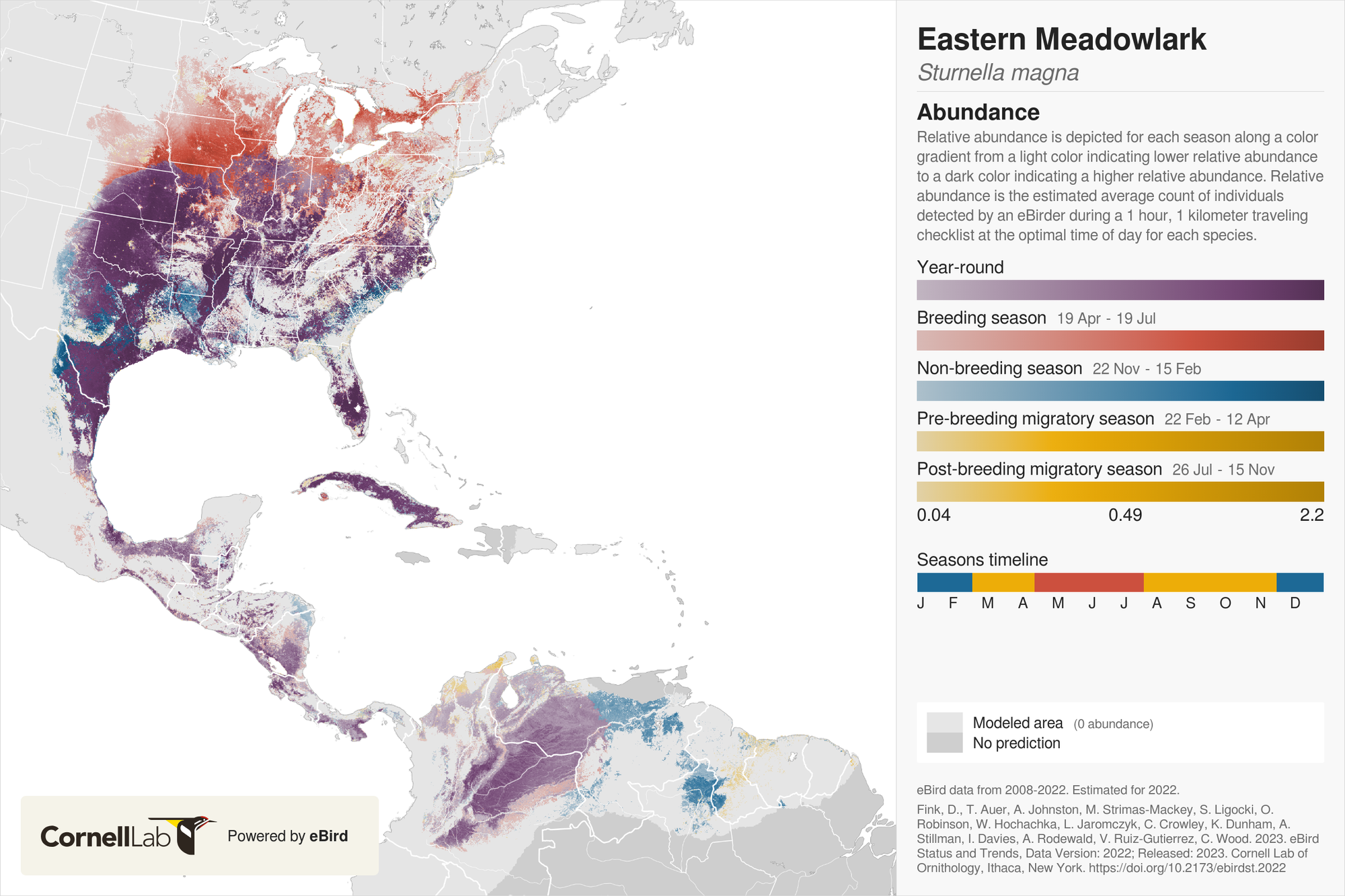

Meadowlarks are not larks; they are, in fact, New World blackbirds, although they, unlike most of their cousins, are not mainly black in color. They were called "lark" because, like true larks, they sing constantly, including while flying. There are three birds in the meadowlark genus: the eastern, western, and Chihuahuan, who look nearly identical and whose ranges overlap somewhat. For my part, we have both eastern and western meadowlarks in Michigan, but the eastern are more common here. This, and the song I heard my birds singing, made me fairly confident that they were eastern meadowlarks. Then again, I didn't get an excellent look at them at first. As I said, this was a surprise sighting, and I didn't have my binoculars on me. I heard them quite clearly while I was near an airfield, and I saw one's characteristic yellow breast and white-edged tail, but that was about it.

Meadowlarks are, as their name suggests, birds of open country. Airfields (like the one I saw mine at), cropland, prairies, or pretty much any place more dominated by grass than by trees is suitable habitat for meadowlarks. They feed on insects, especially crickets and grasshoppers; they are known to stab their beaks into the ground and spread it open while probing, a behavior that their cousins the orioles employ on large fruits. Eastern meadowlarks are found throughout North America east of the Rockies, as well as in parts of the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America. The Great Plains region is the significant site of overlap between its range and that of the western meadowlark. The two birds are basically identical in the field, best differentiated by their songs.

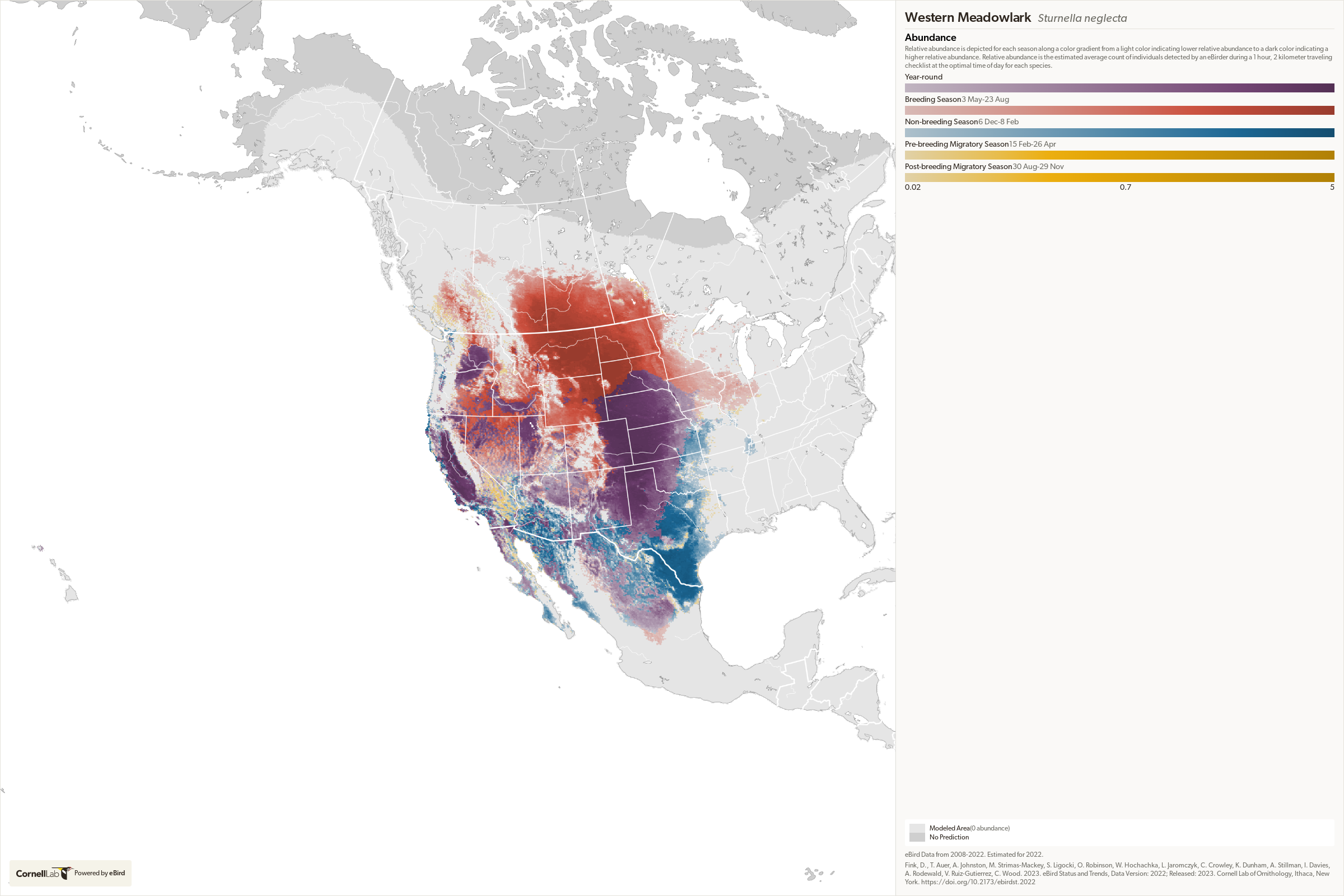

Abundance Maps for the Eastern (left) and Western (right) Meadowlarks

Actually, considering how similar they look, it's unlikely that I'll draw a western meadowlark, so I might as well discuss it a bit here, too. I'll be part of a tradition of mentioning the bird as an appendix. The western meadowlark is known to science as Sturnella neglecta, meaning "neglected little starling" (the icterids were long thought to be wither starlings or close cousins to starlings, due to the two families' close resemblances; this idea is no longer considered true), the name being given by J. J. Audubon in the 7th volume of his Birds of America, in a late portion of the book that featured new species that he'd encountered in his journeys along the Upper Missouri River. Audubon mentions that Lewis and Clark had noticed a meadowlark in that region with a different song, but lamented that "no one has since taken the least notice of it." Audubon admitted that the "Missouri meadow-lark" was quite similar to the already known "meadow-lark", but he catalogued a number of minor but key physical differences and argued for a new species to be recognized.1 His proposal was not immediately accepted but today the western meadowlark is indeed recognized under Audubon's name.

Back to the eastern meadowlark: its scientific name is Sturnella magna, which, confoundingly, means "large little starling". It wasn't named that deliberately; in Audubon's day, they were S. ludoviciana, the "little starling of Louisiana" (the French territory, not the much smaller U.S. state). But taxonomists have since pointed out that Linneaus had already called it Alauda magna in his 10th edition of Systema Naturae. That name means "large lark"2, which is incorrect in that meadowlarks aren't larks but which at least isn't an oxymoron. Rules of precedent hold that the earliest known species name is used, even when creatures are moved to different genera, so "large little starling" it is.

- Audubon, John James. The birds of America. New York, J.J. Audubon; Philadelphia, J.B. Chevalier, 1840. Vol. 7, p. 339-340

- Jobling, J. A. (editor). The Key to Scientific Names in Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman et al. editors), Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca.

Curation Links

The Weird, Analog Delights of Foley Sound Effects | Anna Wiener, The New Yorker

Jack Foley was a prop man and assistant director who developed a method of recording the sounds made by various things to serve as custom movie sound effects. These are rarely the actual things ostensibly-sound-making things depicted onscreen. Today, “foley artists” typically work in pairs, still squishing and scraping things by hand to accompany film scenes.

Habitation of Hell | Athanasius Kircher, Lapham's Quarterly

"From The Subterranean World. In December 1631 an eruption began at Vesuvius that caused a caldera collapse and a tsunami, destroyed farms, and killed up to six thousand people; it was the deadliest eruption there since 79. Several years later, the volcano was still rumbling when Kircher, a Jesuit priest and mathematics professor, came to visit. Kircher descended into the active volcano to record his observations, and between 1664 and 1678 he published his accounts of Vesuvius as well as of Mount Etna and Stromboli, concluding that the planet had a heat source at its center."

Empire of the Sum | Roman Mars & Keith Houston, et al., 99% Invisible

[AUDIO] Keith Houston sits down on the design history podcast to talk about the subject of his book *Empire of the Sun*: the history of the pocket calculator, and how being able to easily and reliably do arithmetic enabled us to do everything else. (39 minutes)

The Lark Ascending | Eleanna Castroianni, Clarkesworld

[FICTION] “They even took the violins. Every last one of them: Amadeus, Josephine, Mulberry, Nestor. They came into the house through the front door, guests without a host, a peculiar band of invited thieves. Plugged into my power station as a seemingly unthreatening household device, I watched them as they ransacked a life. They chatted and joked while scrubbing every nook and cranny, erasing every trace of Papa. They worked fast and efficiently. Within a single morning, nothing in the house would betray he ever lived there.”

See the full archive of curations on Notion

Member Commentary