Book Review | The Black Fleet Crisis

This December I'm doing a 30-year retrospective on Star Wars: The Crystal Star, often named the worst Star Wars book ever written. As part of my attempt to determine if that reputation is deserved, I'm going back to some of the less-remembered entries in the Star Wars library, the ones that aren't likely candidates for an Essential Legends Collection re-release. Are they bad or just overlooked?

| Before the Storm | Shield of Lies | Tyrant's Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Author: | Michael P. Kube-McDowell | ||

| Publisher: | Bantam Spectra | ||

| Length: | 309 pages | 338 pages | 366 pages |

| EE Critic Score: | 8/10 | 7/10 | 8/10 |

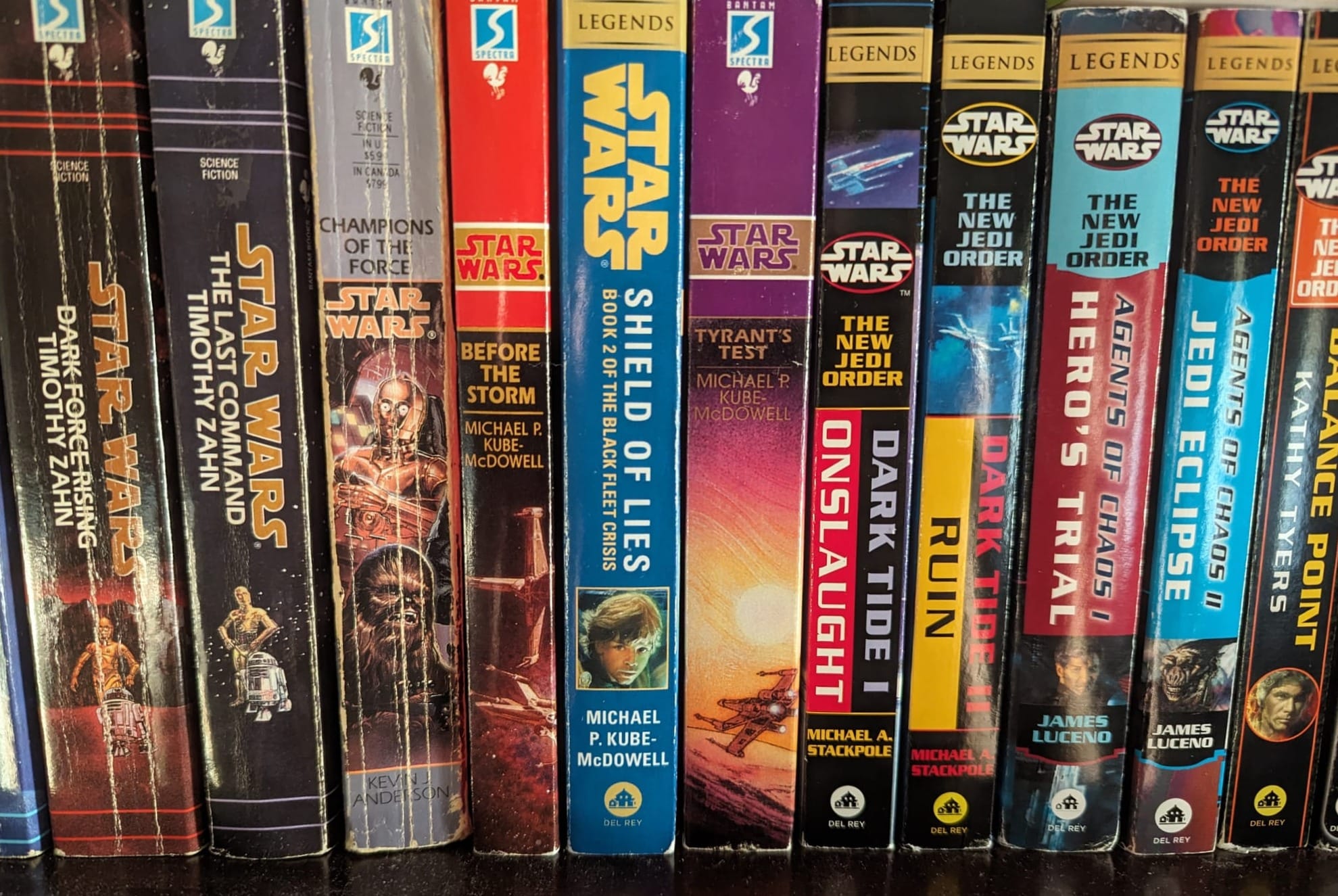

I don't actually own very many Star Wars books.

looks at shelves, sees 78 Star Wars books

Okay, but I don't own most Star Wars books, or even most of the Star Wars books I've read. I'm not a collector. Many of the books I do have were given to me at some point, not sought out and bought. Mostly, I'm happy to depend on Michigan's libraries to get books (Star Wars or otherwise).

I do own the Black Fleet Crisis, a three-volume series by Michael P. Kube-McDowell, who wrote them in the mid-90s in Okemos, Michigan; to the best of my knowledge, McDowell still lives in Michigan's Capital Area. I can't help feeling a sort of connection to these books, as I myself am also a product of mid-'90s mid-Michigan. That's most of why I own these books. But besides that, I like them.

The Black Fleet Crisis, comprising the novels Before the Storm, Shield of Lies, and Tyrant's Test, tells the story of the New Republic's first major peacekeeping conflict undertaken after they become the dominant galactic power. More broadly, these books are about the responsibilities and considerations that come with the transitions from freedom fighters to leaders, both in the story of the titular Black Fleet Crisis and in Luke's story, wherein he begins to consider his future. The books also, somewhat separately, tells the story of Lando Calrissian investigating a lost spaceship holding the treasure of a long-gone species. The books were published between March and December of 1996.

Analysis

McDowell, giving a statement in the lead up to these book's publishing, said of Han, Luke, and Leia, "You can't be a teenaged hero forever". That quote serves as a thesis statement for the Black Fleet Crisis. These are books about not being a kid anymore, both personally for the main characters and politically for the New Republic. The first book, Before the Storm, is a slim volume that serves as a prologue to the rest of the story. It sets up the conflict of the books as something that can't easily be asked with a daring X-Wing run. That results in a story that is more tense than straight-forwardly exciting, more thought-provoking than entertaining.

There are three story threads in these books, and my biggest criticism of these books is that these three threads do not intertwine until the end of the third book, if ever. Shield of Lies, the middle volume, actually breaks the three threads out into three sections, not even cutting back and forth between them from chapter-to-chapter, Lord of the Rings-style. I'll tackle each thread separately in this review, but it's weird to read a book actually set up like that.

The name of the trilogy comes from Han and Leia's thread. In Before the Storm, we open Leia's story with a debate in the New Republic Senate over the commissioning of a 5th Fleet, made to defend frontier worlds from attack by Imperial Remnant forces. Some senators fear that the New Republic military, now that the great Imperial threat is largely vanquished, will turn to subjecting Republic worlds or to conquering independent worlds. Leia, as Chief-of-State, supports Ackbar's 5th Fleet, but she comes into argument with him over how to treat the Dushkan League. Led by Viceroy Nil Spaar, the league is a group of worlds populated by the Yevetha people, a former Imperial slave species who overthrew their masters and seized their warships following the Battle of Endor. Since then they've been keeping largely to themselves. Spaar is asking that the Dushkan League be granted exclusive rights to travel in the Koornacht Cluster, in conflict with New Republic commitments to maintain open access to interstellar space. The worlds of the Koornacht Cluster are not part of the New Republic, so Leia is opposed to any military action to enforce open space lanes, as Ackbar wishes to do. Leia begins to worry that her military leaders are unwilling to adjust to a peacetime role, and are planning to force her out of office.

The Yevetha are a good, unique villain in Star Wars. McDowell does a great job of creating a plausible evil species. The Yevetha are obligate cannibals, their young only mature when feed the blood of adults, thus their culture has developed such that high-status men can kill low-status men, no questions asked, to feed their young. In a lot of speculative fiction, you get hand-wavy phrases like "brutality is in their nature" about orcs or Klingons or whatever. The Yevetha are a proper exploration of what that might actually look like. Paired with that, their experience with the Empire was their first contact with other people, and they responded to learning of others with intense disgust, and now Spaar, having secured, he believes, free reign to act in the Koornacht cluster, opens an extermination campaign against the "vermin" whose presence in the night sky so offends his people. Only one person, a starfighter pilot who flees his doomed world, survives to bring word of the attack to the wider Galaxy.

The Yevetha are a very effective enemy for Leia because they a) aren't' a Galactic-scale threat, or a direct threat to the New Republic, and b) they can't effectively be negotiated with. Leia's two impulses: to argue for peace and to rally people to fight against their oppressors, are blunted against Nil Spaar. The Yevathan war isn't the means to some end, it is the end; the Yevetha want the other peoples dead moreso than they want their planets to live on. There's nothing to offer them but blood. But they are not attacking the New Republic, nor even New Republic allies; most of the worlds purged are Imperial colonies. It seems, at least form the outside, that if the Yevetha are given complete control of the Koornacht Cluster that they'll stay there, so Leia can't rally worlds to rise against them on hte bases of their being a threat to worlds across the Galaxy. Worlds near the Koornacht boundary clamor for membership in hte New Republic, hoping for protection, but many existing member worlds are unwilling to get involved in a war on their behalf. Reading these books today, I couldn't help but draw parallels to real-world events of late in Ukraine, particularly the way the invasion has prompted other Eastern European nations to frantically join NATO. Leia doesn't have the middle-ground options to place the Dushkan League under economic sanctions (they don't trade with outsiders anyway) or to arm the Yevetha's enemies (who are all dead), and, again, the League isn't peer-level with the New Republic, so the two situations aren't one-to-one equivalent, but there are still some odd parallels to find.

Leia's role in these books is...a mixed experience to read. On the one hand, these books really focus on her in her role as a political leader in a smart, deliberate way, unlike too many other stories where she's either sidelined on Coruscant away from the main plot, sent on some unlikely adventure away from her responsibilities, or simply criticized for not being a Jedi like her brother. On the other hand, though, I don't think she's characterized the best here. She's very hostile and paranoid. In fairness, she's facing some very stressful situations, not just immediately but over years of responsibility. And she is facing genuine political threats; when Han is kidnapped by the Yevetha, the immediate outcome is Leia's rivals seizing the opportunity to try to impeach her for being too personally involved in the conflict. But, in Before the Storm specifically, she's needlessly nasty toward poor Ackbar and even Han and Luke catch some stray shots; she acts like all her closest friends are trying to ruin her life. This is while she's still treating Nil Spaar with implicit trust. By the end of that first book, Leia recognizes that she's been mistreating everyone and apologizes, but still some scenes were tough to get through. I was reminded of Poe Dameron in The Last Jedi. Here, like there, I can understand the point the writer is trying to make, but I still don't like watching people being unreasonable, belligerent jackasses for the sake of having them apologize later. In the second two books, Leia is more in her right mind, but I can see some big Leia fans not making it that far.

Eventually, Leia concludes, and is able to convince the New Republic, that the Yevetha must be driven off the worlds they seized, and crippled militarily; the New Republic will take responsibility for maintaining international order, as it were. As the 5th Fleet gathers at the Yevethan homeworld of N'zoth, they get unexpected help from two sources: the Imperial naval officers enslaved by the Yevetha execute a secret plan to seize back their Black Fleet, sending all Nil Spaar's Star Destroyers to the Imperial holdouts in the Galactic Core (and dumping Spaar himself out into hyperspace). And Luke enters the scene with some new friends.

Luke's story in these books often feels a bit drawn-out. He has less to do than Leia, but the structure of the books means he must do it in roughly the same number of pages and over roughly the same amount of time. Like Leia's story, his is about trying to find one's place in the world one has created. We open with Luke in a weird mood, feeling that it's time for him to step back from leading the Jedi to focus on gaining a better understanding of the Force. He leaves Streen in charge of the Academy on Yavin 4 and secretly travels to his father's old castle on Coruscant, where he spends a few weeks meditating. While there, he is found by a woman called Akanah, a member of a group of Force-users called hte Fallanassi, who was separated from the rest of her people as a child when the Empire began hunting them down. She asks Luke for help in finding them and tells him that a Fallanassi woman named Nashira is his mother.

Luke goes to Leia (who you'll remember had some fleeting memories of their mother) to try to get some sense of whether Akanah is telling the truth. Leia is, as I mentioned, not in a great place right then, and she tells Luke that she doesn't care about their mother. If she's alive she's had plenty of time to come forward, and if she's dead then there's no point. Leia sees her past as nothing but pain and death, and her idea of family rests in the future with her children.

“My children are going to have normal family stories to tell their children, little funny stories about everyday nothings, stories where no one dies too young or has to carry a burden of shame. I’m going to see to that, with your help or without it—”

(As an aside, that quote was a real gut-punch to read now, knowing what happens to Han and Leia's children as the old EU stories played out.)

So Luke goes off with Akanah to search for the Fallanassi. On the way, she questions how he (and the Jedi broadly) can be good if they kill people. The Fallanassi are strict pacifists, who use the Force (or the "White Current", as they call it) to conceal themselves and others from perception. Which brings me to something McDowell has said regarding the Fallanassi: "The Jedi path is an intensely masculine one–what is to say that there aren’ t alternatives founded on different premises?" Now, to a modern Star Wars fan, calling the Jedi "intensely masculine" seems a strange thing to say; there are, after all, many female Jedi in the Star Wars cast: Ahsoka Tano, Bastilla Shan, Avar Kriss, Jaina Solo, Tahl, Aayla Secura, just to name some who've been major characters. But, in the '90s, that was less true. Sure, you had Tione, Kiara Ti, and Cray Mingla among Luke's students, and you had Nomi Sunrider noted among the ancient Jedi, but all the Jedi in the Original Trilogy and the majority of those seen elsewhere were men.

Then again, I don't think that's exactly what McDowell is getting at. I think, in contrasting his "masculine" Jedi with the feminine Fallanassi (all of whom we see are women), he's contrasting two ways to defeat one's enemies: through violence and through deceit. Any sort of "men vs. women" comparison is going to be an exercise in stereotyping, so let's look at a very stock character: the high school bully. In high-school stories, the bully is usually male and is usually shown taunting, menacing, or outright beating the hero; they are directly aggressive, even violent. Contrast this with the high school "mean girl". She often won't even verbally attack her victims to their face, rather working by spreading nasty rumors behind their backs. In the classic bully character, boys are violent, and girls are deceitful.

Similarly, here, while the Jedi are sword-wielding knights, the Fallanassi are unarmed illusionists, adept at hiding themselves and others from threat of harm, as they are doing to the people of a world in the Koornacht cluster where Luke and Akanah eventually find them. Along the way there, Akanah questions how Luke can bring himself to kill others. We find that Luke knows the exact number of people killed when the Death Star was destroyed (1,205,109) and that each death weighs on him. When Akanah asserts that she and the Fallanassi are able to live without violence, that's an attractive prospect to Luke.

Once they find the Fallanassi, Luke convinces them to come to the aid of the New Republic Fleet, using their illusions to make the armada appear much larger in order to force a Yevethan surrender before a protracted war ensues. Afterwards, we find out something that modern readers will already have guessed: Akanah was lying; she didn't know Luke's mother; she just said she did to get him to join her, so that she might convince him to abandon the Jedi bath and join the Fallanassi. I should note that while McDowell was writing these books, George Lucas was already writing The Phantom Menace, and developing the character of Padmé Amidala. At the time, though, I suppose it could have seemed to readers that readers might have believed that Luke and Leia's mother really was Nashira. The fact that it turned out to be a ruse might make Luke's story in these books feel like a waste of time, but it's clear rather early on that the point of his story isn't really his mother; it's about whether the Jedi are truly good. In the end, that question is not fully answered; rather, the question becomes whether the Fallanassi are any better. When the Fallanassi leader prompts Akanah to admit that Nashira was not Luke's mother, he dismisses her excuses, saying he can't trust anything she told him. He and the Fallanassi part ways.

Now, framing violence vs. deceit in terms of men vs. women, while I get the logic in terms of storytelling patterns, I think is a bit at odds with reality, and is, I feel, needlessly prone to starting tangential arguments. Just as easily you could frame it as civilization vs. barbarism, as we see it in the conflict between the New Republic and the comparatively less-developed Yevetha. There's men and women on the New Republic side, and while the Yevetha are pretty male-dominated, Nil Spaar has the support of the women of his world. This isn't framed as masculine vs. feminine, but it's the same theme of violence vs. deceit.

We see that conflict in the way Nil Spaar presents himself. In his dealings with Leia in Before the Storm, and later in his public statements before the Galaxy, he's very deceitful, working with spies and feigning victimhood, but he finds doing so distasteful and weak. The often dishonest and backstabbing nature of representative politics lacks the straightforward honesty of Yevethan duels. By the end he can't keep up the façade; his final address to the Galaxy is simply several minutes of him beating Han Solo to a pulp and screaming into the camera. He embodies pre-modernity barbarism.

The question of whether violence or deceit is worse seems, at first glance, simple: would you rather be killed or lied to? That's not a hard question to answer. Throughout the world, attacking someone is almost always illegal (with some exceptions) while lying is rarely a legal matter (again, with some exceptions). But that doesn't necessarily make deceit a preferable path in serious conflicts. Here, when the Fallanassi conceal the people of J't'p'tan from the Yevetha, that's a strategy that requires constant upkeep. The Yevetha remain in the skies, and thus remain a threat. Only when the Fallanassi pair with the 5th Fleet, an agent of violence, is that Yevathan threat removed from J't'p'tan. Deceit is bloodless, but it's all-consuming. A victor can lay aside their sword after a battle and live a life of peace, but a convincing liar often must lie forever. What happens when a necessary evil becomes something you must perform forever? The Yevetha, from biological necessity, must always kill, and we saw what that turned them into.

We don't really see how pervasive deception is among the Fallanassi. Beyond these books, they don't appear much more in Star Wars. Jacen Solo visits them during his post-Yuzhann Vong War pilgrimage to learn of other Force traditions. And they do exist in the new Canon, having apparently appeared in a few comics, and being the creators of the Force technique Luke used to project his presence from Ach-to to Crait, to confront Kylo Ren, in The Last Jedi. But it's hard to make a judgment from these few appearances. In the end, I don't think I'd call them evil, since they seem to practice self-sacrifice in the face of true evil, as do the Jedi. Beyond that, I can't expect the big thematic questions at the core of these books to be answered neatly; like the Alphabet Squadron trilogy, the Black Fleet Crisis taps into serious real-world debates, and what hasn't been resolved in reality can hardly be resolved in fiction. The specific scenarios may be resolved in a specific way, leading to a specific sort of happy ending, but the broader questions remain.

There are two main characters I haven't spoken about yet: Chewbacca and Lando. Chewbacca actually leaves the scene pretty early on in Before the Storm to visit his family. Yeah, McDowell saw the Holiday Special and decided to bring those characters back. And it actually works. Chewie takes the Millennium Falcon to Kashyyyk to guide his son through a coming-of-age ceremony. He's not in the rest of Before the Storm or in any of Shield of Lies (the cover of which is the only place in the book where the Falcon appears) but he does play a big role in Tyrant's Test. This third book actually contains something pretty rare: dialog from Chewbacca. Chewie was never captioned in the films, and in the books, similarly, we usually only get statements that he growls or roars, and the other characters' reactions to him. But in Tyrant's Test he speaks with his sone, his wife, and other Wookiees and we get that as actual written dialog.

Chewbacca's story in Tyrant's Test is pretty simple but well-done: he gets word that Han Solo was captured by the Yevetha, so he, his son, and several other Wookiees go to N'zoth to rescue him, with his son earning his manhood in the process. We get some nice looks at Wookiee cuture, and I always enjoy a story where Chewie is treated like a person and not Han's pet. Actually, I found it a little weird that, in the beginning of the first book, it's Leia who argues that Chewie should get some time away, and Han who grumbles, even though, in the films and elsewhere, Han was consistently the more respectful of Chewbacca.*

As for Lando: his parts of the books are both some of the best and some of the worst parts. They're some of the best because Lando is the character whom McDowell writes the best. His is the best Lando I've read in any book. Lando doesn't get a personal crisis to deal with, because Lando is a character who goes through a perpetual cycle: he seeks a good life, works to solidify his position, then gets bored and goes off on some adventure to seek some new good life. He literally states as much to Drayson at the beginning of Before the Storm:

Drayson folded his arms over his chest. “So—what can I do for you?”

“Wrong question, Admiral,” Lando said. “What can I do for you?”

“Pardon?”

“I’m bored,” Lando explained simply. “I go in business, I make a little money, I lose a little money—the game isn’t interesting anymore. Someone throws a title at me, and I pick up the pieces someone else dropped—until one day I realize I’m sitting behind a desk, turning into you. There’s no challenge in smuggling, unless you want to go to the Core—and I’m too smart to be that dumb. And there’s hardly a scrap anywhere in twenty parsecs worth getting dirty for. That’s why I’m here.”

When Drayson sends him to investigate a derelict ship left by an extinct species, Lando brings along Lobot, who we actually rarely see outside of The Empire Strikes Back, and also Artoo and Threepio. They sneak aboard the derelict in defiance of their Naval Intelligence handlers, and wind up trapped aboard as the ship starts jumping through hyperspace. They have to figure out hte purpose of the ship, whose alien design baffles them, in order to learn how to control it and make it back to someplace where they can get off. It's essentially a more exciting version of Rendezvous with Rama, starring Lando Calrissian. It's great.

But what does any of that have to do with the Yevetha? Nothing. That's the problem. Lando's story does not tie-in, plot-wise or thematically, to the rest of these books. Luke shows up at the very end, but otherwise nothing he, Han, Leia, or Chewie are doing has anything to with what Lando's doing. And while his scenes are part of the regular chapters in Before the Storm, they're all kept in one of those sections of Shield of Lies that I talked about, and in Tyrant's Tests they're relegated to inclusion as "interludes" between chapters. By this point, it's increasingly clear that Lando's story won't tie into the rest of the book's events, and each interlude feels like a real interruption to the main story. Lando's stuff is good, it really is, but I'd much rather have had it as Lando Calrissian and the Treasure of the Qella, a separate book, rather than have it scattered throughout three unrelated books.

Honestly my biggest complaint about this trilogy is that it is a trilogy. I think if you took all of the Lando stuff out and put it in its own book, and tightened up Luke and Akanah's story a bit, you'd have a good single-volume long-ish novel that's a straightforward read. As it is, it's structured very awkwardly. I'm not sure if this came from McDowell or from someone in publishing, but it genuinely did throw off my reading enjoyment, of Shield of Lies especially.

The key adjective describing the Black Fleet Crisis today is "forgotten". They're rarely talked about. And while I liked these books, I can see why: they aren't very influential. There are no characters introduced here who went on to be a major part of anything else. The war with the Dushkahn League had limited Galactic consequence. Later Star Wars works didn't reference it much beyond a mention here and there (the biggest being when N'zoth was destroyed by the Yuzhann Vong). I'd rank these books just behind where I'd rank Zahn's original Thrawn trilogy, in terms of quality, but they're nowhere near as essential reading.

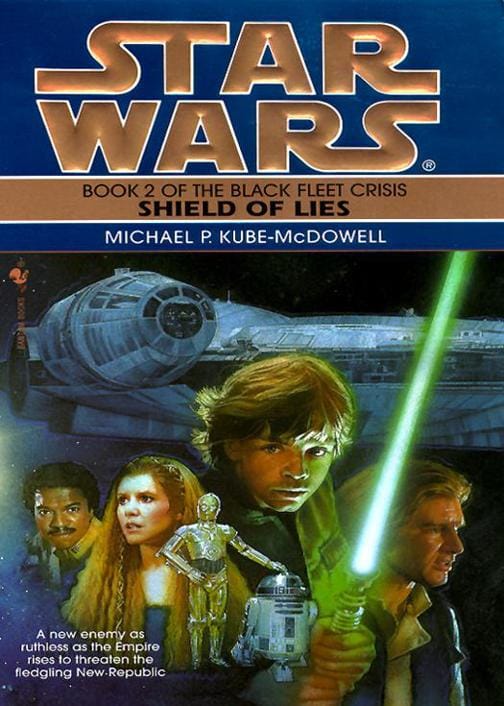

A note about the covers: as always, Drew Struzan can compose a nice assemblage of Star Wars imagery, but, besides Lobot featuring on the front of Before the Storm, none of them seem particularly suited to the books' contents. The cover of Shield of Lies, especially, could be the cover to nearly any New Republic-era book besides Shield of Lies, since, as I mentioned, the Millennium Falcon does not feature in that book. Also, I have original-style editions of Before the Storm and Tyrant's Test, but a "Legends" variant of Shield of Lies, and I'm sad to report that the new printings of these books do not feature the artwork wrapping around the spines.

One more thing that stuck out: the New Republic's 5th Fleet is placed under the command of General Etahn A'baht. Shouldn't a fleet officer be an Admiral? Well, in Tyrant's Test, we learn that A'baht's people have their own fleet, and their fleet officers are called "generals". A'baht was allowed to keep his rank of General when he joined the New Republic fleet. That's an explanation, but I've been a Star Wars fan long enough to recognize "Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs"-style explaining away of flubs when I see them.

Recommendation & Rating

Michael P. Kube-McDowell's Black Fleet Crisis (Before the Storm, Shield of Lies, and Tyrant's Test) is a hidden gem of Bantam-era Star Wars. It delivers a thought-provoking narrative while staying true to Star Wars themes. Nil Spaar is the second-best villain of '90s Star Wars, behind Grand Admiral Thrawn. Chewbacca gets a real chance to shine in the third volume. Lando Calrissian's scenes are some of the best writing of the character, though they would have worked better in their own book. The second volume suffers somewhat from being divided into three parts happening concurrently but read seperately.

While younger readers might find these books a bit less action-packed and youth-focused than they'd like from a Star Wars story, adult fans of hte franchise who haven't checked these books out yet would do well to do so. I rate the Black Fleet Crisis trilogy:

Before the Storm

8

/10 — Without significant negative worth. Able to be recommended to the interested without reservation.

Shield of Lies

7

/10 — With some measurable negative worth, but overall a positive experience. Above average and able to be sincerely recommended.

Tyrant's Test

8

/10 — Without significant negative worth. Able to be recommended to the interested without reservation.

* After The Force Awakens came out, I and a lot of other people noticed how Leia went to hug Rey (someone who she'd never met before) after Han's death, rather than Chewbacca, who was also right there, and drew parallels to how she didn't give him a medal at the end of A New Hope and generally didn't seem to like him. I was all set to write my case that Leia's a bit racist towards Wookiees, but then Carrie Fisher died and I thought it would be in poor taste, and I've just never gotten around to it since.

Member Commentary