Running Commentary 3/27/2023

Hello,

We're closing out March this week. This has been a lousy month for me in a lot of ways. The weather's been terrible, and because the weather's been so terrible I missed most of this year's Spring duck migration. Even this newsletter was a little overwhelming as BattleBots, The Bad Batch, and The Mandalorian all ran at the same time. Thankfully, this week and the last had no BattleBots, and next week will see the finale for The Bad Batch, so there's only one more week of triple-decker "Watching..." sections. Here's to a better April.

Anyway...

Watching...

The Mandalorian

After last week's extra-long episode, this week's is a quick half-hour, but full of great moments. Here are my notes:

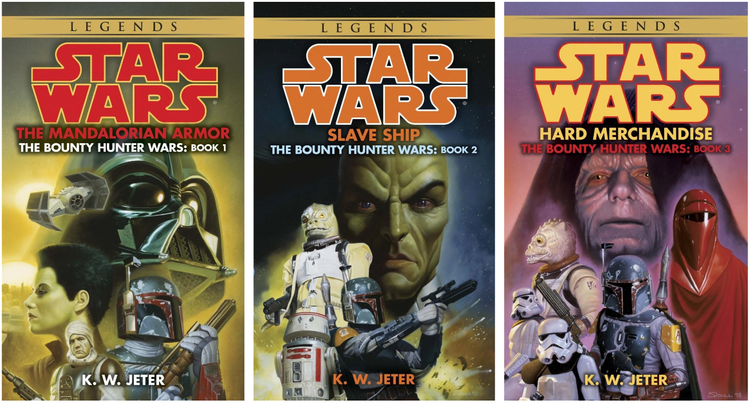

- It's weird to say this, but this episode is probably the best look at Mandalorians that we've had so far in The Mandalorian. Sure, we've seen a lot about their culture up to this point, but this is the first episode that's just shown Mandalorians going about their lives, without either some quest to carry out or some Imperial attacks to fight off. The Children of the Watch seem like the closest thing to Traviss Mandalorians that we've seen so far in Canon. Traviss didn't have the helmets always rule, but the other elements, such as the strong tradition of adoption, warrior code, and combat training from youth, are all straight from Traviss's books.

- I am curious as to the logistics of living as part of this Mandalorian covert. They seem to be alone on this planet full of dinosaurs, without a spaceship, based on how they had to rely on only their jetpacks to pursue the raptor until Bo-Katan showed up. They live in natural caverns and can probably hunt for food, but where do they get ammo and other supplies? Back on Nevarro they had Djarin working as a bounty hunter to support the folks back in the sewers, which was at least a plausible situation, even if it was a little weird. I'm not sure how they're supporting themselves now.

- Back when she first appeared on Andor, I declared Leida Mothma to be the most obscure existing character to have been made a part of the official Canon, and, as far as I'm concerned, she still is, but Kelleran Beq is up there, too. (For those who don't know, Kelleran Beq is a Jedi character created to serve as the host of The Jedi Temple Challenge, a children's competition show made for the official Star Wars Kids YouTube Channel.) Having Beq be the one to save Grogu from the attack on the Temple was a great way to feature a recognizable face without making the world feel too small.

- There's just something about watching a beskar forge that makes people remember their traumatic past, apparently.

- I honestly expected Grogu to use the Force to deflect Ragnar Vizla's darts, or maybe even throw them back, but what we got worked too.

- Bo-Katan is definitely going back to try and ride that Mythosaur.

The Bad Batch

The final episode before the two-part season finale really gave the impression that this season really has a three-part finale. Here are my notes:

- This episode kind of had quite a bit happen and nothing happen, all at once. Largely, this was an episode about finding things out. Echo and the rest of the Batch find out that Crosshair turned on the Empire, and discover Tantiss. We, the audience, discover what Echo and Rex have been doing this whole time (about what we expected, really). But nothing really happens. A great deal of time is spent on Crosshair's failed attempt to escape Mount Tantiss, which didn't tell us anything new or change any situations. This episode was all prologue to the finale otherwise.

- Rex's group has apparently kept their blasters on stun even for the new stormtroopers. I kind of get why Rex didn't want to kill his brothers during Order 66, but the way The Bad Batch has handled things since has been a really obvious play at kid-friendliness that's unearned and doesn't work very well.

Reading...

Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel

I've noticed something interesting about the way I write these newsletters: when I write the "Watching..." section, I do so presuming that my reader has also watched whatever I watched, and I discuss spoilers freely. The the "Reading..." section, though, I write presuming my reader has not read whatever I have read, and I try not to give too much detail away, especially about fiction books. Well, the most recent book I've read was Goodreads's pick for the best science-fiction book of the past year, so quite a few people had read it before I did, and besides, it's a tough book to take about without really talking about it, y'know? So if you haven't read Sea of Tranquility, I'll say this: the book was well-written, engaging, and not too long. The premise was clever, and the story told did it justice, although I don't think the book had the intended emotional impact on me. Beyond that, I'm going to spoil the book.

Sea of Tranquility is a time-travel story, although one more interested in telling a story across different time periods than in working out the logic of continuity paradoxes. Combining time travel with the suggestion that the characters live in a simulation was an unusual twist on the concept.

The opening chapter, set in early 1900s Canada, was an unexpected introduction to something I'd never heard of: remittance men. Apparently, it was common practice among wealthy British families of the day to send any sons who had embarrassed the family or generated a controversy off to Canada, along with a regular stipend and a warning not to come back to Britain. As much happens to the book's first protagonist. The second protagonist was apparently borrowed from Mandel's earlier work, The Glass Hotel, which explains why she and the other characters in her story felt so over-realized for such ultimately minor figures. The third protagonist is a sci-fi novelist stuck in quarantine whose self-intertishness I took as deliberate. The fourth, and main, protagonist is a sort of time-cop who gets dispatched to investigate how the other three all seemed to have the same vision at different times. The fact that all three people go on to die in a pandemic is part of a motif, but doesn't actually have anything to do with the visions; rather, it was reality breaking down because of the time cop meeting with them all, plus with another guy who was himself exiled to the past and older, continuity, cause-and-effect paradoxes, etc., etc.

What holds the book together is how well-written it is, on a prose level. Reading it was a pleasure. But what pulls the book back apart again is that what's written so well is kind of a hollow story. The point of speculative fiction, as I see it, is to sort out what about society is universal truth and what is a product of specific history and circumstance by envisioning a different society with a different history and set of circumstances. Such fiction can take a lot of different forms, but that's the core of it. This book's answers to those questions are that humanity's ability to ask and answer questions is always improving, and will likely be much improved in the future. What remains true through time is that the answers to big questions are largely irrelevant. The moral of the story that we're left with at the end is that the best you can hope for in life is a quiet home in the country where you can take up a hobby. It's an essentially Epicurean, and, with respect to my northern neighbors, an essentially Canadian thought. And while I'm not inclined to dismiss it out of hand as a philosophy, I can say that it's an underwhelming animating spirit for a story's plot. Sea of Tranquility is well-titled. Like its namesake, it's expansive, bleakly beautiful, but ultimately rather empty.

Bird of the Week

This week we have another crane. In fact, we have probably the strangest crane. The Blue Crane is a small crane with the smallest range of any of its kind; they are found almost exclusively in South Africa, with some bleed-over into neighboring countries, and a separate, isolated population of several dozen living in the Etosha Pan, a dry salt lakebed in northern Namibia. They are, unlike other cranes, not fond of water, nesting and feeding not in marshes but in the grassy uplands of the highveld. Blue cranes do move seasonally, generally keeping further uphill during the summer and heading lower in the winter (as they'll be starting to do now), but they are otherwise not migratory. While not migrating is not unheard of in cranes, it is unusual for an entire species, and it's very surprising considering the blue crane's close cousin, the demoiselle crane, makes a seasonal trip over the Himalayas, among the most punishing and impressive migrations of any creature, bird or otherwise.

Blue cranes stand between three and four feet tall. They aren't really blue; rather, they're a sort of cool gray. Their long, wispy "tails" are actually formed by the long plumes of their wings' inner secondary coverts. They and the demoiselle crane have completely feathered heads, lacking the bald patches of red skin that usually mark crane faces. Blue cranes are not quite crested, but long feathers on the backs of their heads give them a somewhat bulbous or cobra-like appearance. Their faces have a gentle, dove-like sweetness that belies a rather vicious territoriality. While generally not a threat to anything larger than a grasshopper, blue cranes are quite aggressive about defending their eggs and colts, striking out at any animal that gets near them, even harmless creatures such as antelope.

The blue crane is also known as the paradise crane or the Stanley crane, the latter name being given in honor of Henry Stanley, the Welsh-American explorer famous for finding David Livingstone. Stanley holds a complicated position in African history: as an explorer, he improved the understanding of the geography of inland Africa; as an abolitionist, he was instrumental in ending the slave trade out of Zanzibar, which had remained in place after slave exports out of western Africa to Europe and the Americas had ceased. But his attitude toward Africans otherwise, which informed broader Western sentiments, was highly patronizing, and his exploration on behalf of Leopold II of Belgium aided in the establishment of a regime whose exploitative cruelty was decried even by other imperial powers of the day.

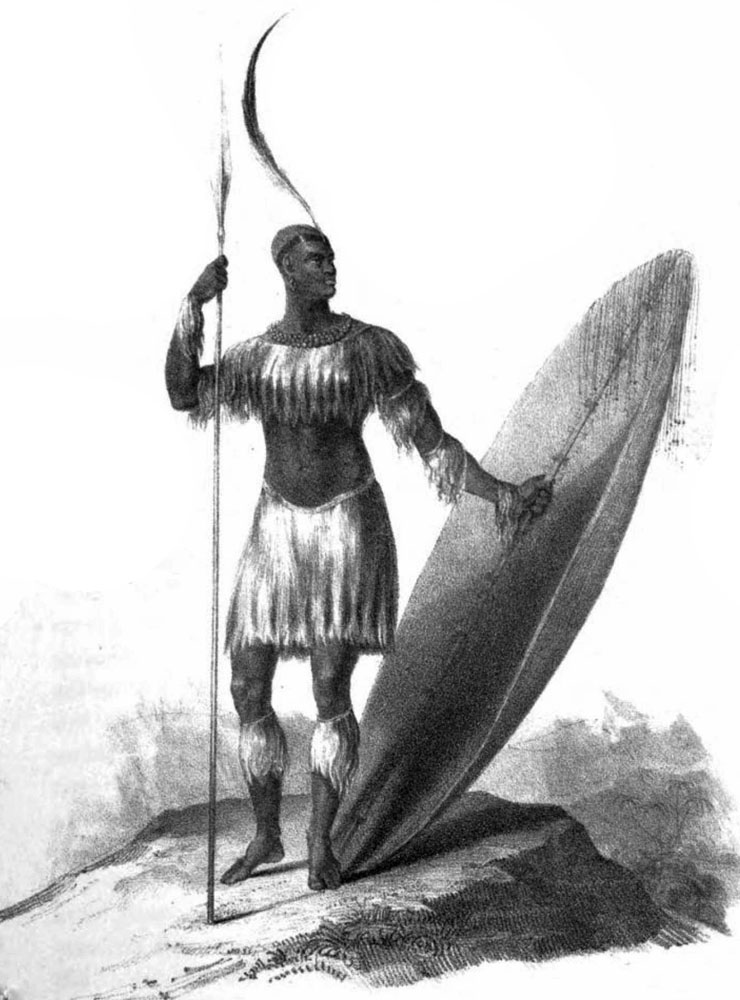

The Xhosa and the Zulu both call the bird "indwe". These people traditionally would wear the long feathers of the blue crane as a mark of honor. In more modern times, the Isitwakandwe Award (the name of which literally translates to "wearer of blue crane feathers") has been given to South Africans who fought against apartheid. The blue crane is the national bird of South Africa, though neither this distinction nor its traditional significance has been fully able to prevent population declines in the face of farmland expansion into the highveld.

The German zoologist A. A. H. Lichtenstein first described the blue crane as Ardea paradisea, or the "paradise heron". It has retained that specific name, though it has since been removed from the heron genus. Which genus it does belong to depends on what source you check; some place it in the main crane genus Grus, while others (both more and less recently) place it and the demoiselle crane in the genus Anthropoides. That genus has a name meaning "womanlike" and is specifically referencing the demoiselle crane, whose common name comes from the French for "young lady"; apparently, this name was given by Marie Antoinette, in reference to those birds' delicate, ladylike appearance.

Curation Links

The Great Canadian Baking Show Is a Pile of Wet Dough | Alex Tesar, The Walrus

A look at how Canadian culture is often little more than the culture of other Anglophone countries soaked in a syrup of North Woods Kitsch. The Great Canadian Baking Show, a localization of the popular Great British Bake-Off that simultaneously fails to differentiate itself as intrinsically Canadian and fails to properly copy the original.

Bad Blood, Bad Science | Alexis Pedrick, et al, Distillations

[AUDIO] “The word “Tuskegee” has come to symbolize the Black community’s mistrust of the medical establishment. It has become American lore. However, most people don’t know what actually happened in Macon County, Alabama, from 1932 to 1972. This episode unravels the myths of the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) Syphilis Study (the correct name of the study) through conversations with descendants and historians.”

How do you Solve a Problem like Susan Pevensie? | Kat Coffin, A Pilgrim in Narnia

Really only of interest to those who’ve read The Chronicles of Narnia, this is a look at how sloppy literary criticism can propagate through the years.

Eight Episodes | Robert Reed, Lightspeed Magazine

[FICTION] “With minimal fanfare and next to no audience, Invasion of a Small World debuted in the summer of 2016, and after a brief and disappointing run, the series was deservedly shelved.”

See the full archive of curations on Notion

Member Commentary